I find myself in a strange situation. I’m an urbanite with resolutely ungreen and unexperienced hands. To prove it: Spring onions – spring onions, I say! – died on me this winter. For three weeks this August, I find myself trying to understand how people grow coffee and the challenges that they might be facing from climate change. What’s more, I find myself pretending to be an expert not only in agriculture, but also speaking about it in a language I only started learning over a week ago. The people at or connected with INCAPER whom I’ve met and am working with here are experts be it in their study or their work.

It’s hard to imagine how people actually grow crops unless you actually go and see for yourself. Farmers here in Brasil don’t necessarily focus on coffee, just like what I saw in Vietnam. On Friday I had the opportunity to interview a guy whose main crop was coconut, and another, papaya. Both grow coffee beneath the shade of coconut/papaya – they commented that they appreciated the security and convenience of that particular pairing. Their largest concern, they said, was productivity and cost. This seems to be the largest concern, especially for small-scale, family agricultores – staff at INCAPER agreed as well. These growers have ten, twenty-five, forty, hectares of a variety of crop. This is considered production on a small scale, thus they don’t necessarily grow enough to guarantee a fixed price on the very volatile market. In the following week

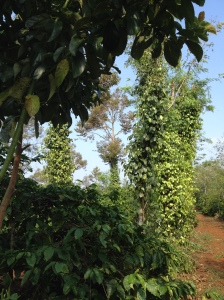

Alongside this issue of livelihood security sits the issue of conservation of endangered habitat. Coffee over this region is grown over cleared Atlantic rainforest, known as the Mata Atlântica here in Brazil. The Mata Atlântica, like the Amazon, is a biodiverse biome that crosses national borders. It extended historically from the south-eastern region of Brazil down to Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina, and is known for its primate species, a majority of which are endemic and endangered. As is common among areas of rich biological diversity, Mata Atlântica has disappeared much faster than its interior neighbor, the Amazon – its nutrient rich soils are sought after to grow coffee, mamão (general term for papaya), cattle, Piper nigrum and others.

It was interesting to be able to see, in person, the matrix of critically endangered biome interspersed among swaths of monocultures and polycultures here in Linhares, which is home to the Federal Reserve of Sooretama, one of the remaining protected areas of Atlantic Rainforest.

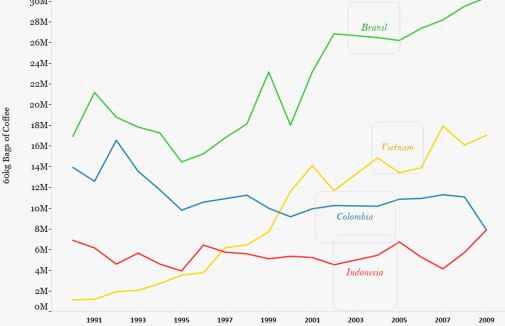

Brazil has been incredibly focused and successful in technological research and importantly, the transfer of these technologies to farmers towards the aim of productivity. Two species of coffee grown in Brazil are arabica and robusta, the latter known locally as conilon. Brazil produces way more arabica than conilon – a quarter of the coffee grown in Brazil in 2015 was conilon, a quarter which is in the state of EspÍrito Santo. In this state just 60% of coffee is conilon, but that alone gives it the title of second-largest producer of coffee, one step behind all of Vietnam, a country more than 7 times larger in size. So if everything goes according to plan I’ll be able to meet more cool people on my side of the world who’re doing cool things and draw some pretty interesting cross-comparisons.

Checking out.